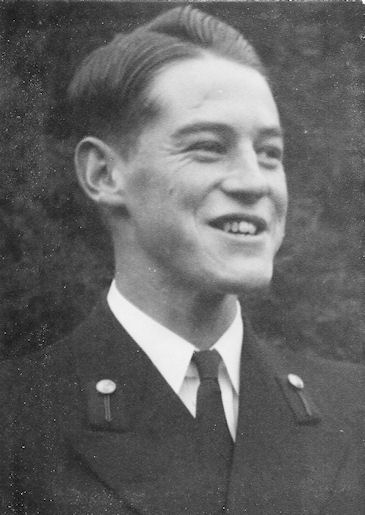

John

Begent 1925-1994 John

Begent 1925-1994Photo taken in 1943 |

My father John Begent was born in 1925 and lived as a boy in Ewell, Surrey. He was educated at Kings College School, Wimbledon. From 1943 - 47 he served in the Royal Navy on small ships in the Mediterranean clearing mines as the Allied forces liberated Greece and the Greek Islands. In 1948 he joined the British Colonial Service and found himself posted to Bekwai in the Ashanti region on Ghana (then the Gold Coast) in West Africa. The following about his experiences during the 2nd World War is an extract from his memoirs written for his grandchildren in 1992.

|

|

THE SECOND WORLD WAR: A PERSONAL REMINISCENCE My home was, and still is, at Ewell, 14 miles south-west of London. From 1938 I attended Kings College School, Wimbledon, travelling daily six miles up the line towards London (Waterloo). I was 14 at the outbreak of war. On 3rd September 1939 I was at a Crusaders (Bible Class) Camp at Thurlestone in South Devon. That morning we were all gathered in the large marquee to listen to a broadcast by the then Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announcing that, following the invasion of Poland, Britain was now at war with Germany. The camp broke up the next day, and we returned home by what seemed a very slow train. The main stations in London were thronged with extra travellers, such as Army, Navy and Air Force Reservists returning to their units, and children being evacuated to country districts to avoid the expected bombing. That came, but not until the following year. "A.R.P." Air Raid shelters were prepared. For households in vulnerable areas individual "Anderson" shelters (named after the Home Secretary of the day, Sir John Anderson) were available. These consisted of a short tunnel of corrugated steel bolted together; the shelter was then partially sunk in the garden soil, the excavated earth being banked on top. The main problem was that, being below ground level, the rain tended to collect in them. The more affluent, like our neighbour, had a shelter built of bricks, with a solid concrete roof and floor. This still stands. My father and mother, who had experienced German airship ("Zeppelin") and aircraft ("Gothas") raids during the 1914-18 war, both joined the "A.R.P." and underwent training as Wardens. Their job was to patrol their area at night and check that no lights were showing - every house and building had to be "blacked out" and all street lighting was extinguished to make it difficult for an enemy bomber pilot to determine exactly where he was. Traffic lights continued to operate, but each lamp was screened so that the light showed dimly as a "+". In the event of an air raid they were to see that people took cover in shelters. When bombs dropped they were expected to be the first on the scene, and summon help that might be needed from fire and ambulance services. My father made sure that at home we were equipped to deal with small incendiary bombs which could be dropped in their thousands to start fires. There was a "stirrup pump" and hose with which thin jet of water from a bucket could be directed at the fire, a galvanised bucket to hold sand with which to smother the blaze and a long handled scoop with which, in theory at least, the bomb could be picked up and carried where it could do no damage. I still have the stirrup pump and the scoop. Rationing The food shortage, which was aggravated by the sinkings of ships by

German submarines (U-Boat = Untersee Boot), led to the "Dig for

Victory" campaign to encourage everyone to grow as much food as

possible themselves. Not only was the whole of the end of our garden

devoted to vegetables, but my father also took an allotment i.e. a patch

of ground in an otherwise uncultivated area, so as to grow more food.

He wasn't a very enthusiastic gardener, but he felt it to be his duty. The "phoney war" "Blitzkrieg" The summer of 1940 The Battle of France had been lost. Now it was the Battle of Britain. No one doubted that the Germans would invade. But first they had to gain command of the air. After attacks on shipping and coastal ports the Luftwaffe (German air force) turned its attention to the RAF fighter airfields, and I had my first, albeit remote, experience of war. Seaside holidays being out of the question in 1940, my father decreed that we should cycle for recreation. An Ordnance Survey map was very necessary because all signposts had been taken down so as to provide no help for invading forces. One Sunday in August we rode up to Headley Heath on the Downs south of Ewell. Up there was an Observer Corps post; their job was to report all aircraft movements by telephone to a headquarters. Suddenly a voice said "Here they come". Looking up I saw a large formation of enemy bombers heading north. I can still see them in my mind's eye, the sun reflecting off the light coloured undersides of the aircraft. Then the sounds of gunfire were heard, distant at first. RAF fighters were attacking. Then someone from the Observer Post shouted "Get down !" Low along the road to the east came two aircraft, very fast. They were a German Me109 fighter and his pursuer, an RAF Hurricane, its guns firing. We dived for cover in a ditch as stray bullets bounced off the road. Despite injunctions from my mother to keep my head down, I couldn't resist watching as both aircraft disappeared from view behind some trees. Quite what happened I never found out, but little later the Hurricane returned alone. Everyone cheered. The Luftwaffe failed to gain control of the air over Southern England, and Hitler called off the invasion, although we didn't know that at the time. Raising money for Spitfires became a national pre-occupation. If you could afford £5000, you could have one named after you. A lot of aluminium was used in their construction, and an appeal went out for households to donate their aluminium utensils. My mother was quick to respond. Our kitchen had a set of good quality aluminium saucepans. All these went for Spitfires, except one, which I still have. It had been used for boiling eggs (as it still is), and she didn't think it was clean enough to be used in a Spitfire ! The night "Blitz" My parents spent almost every night on duty at Post 25, a brick built shelter close to the local Primary School. Mother was the telephone operator, reporting to the local ARP headquarters; she did a great deal of knitting. My father patrolled Post 25's area with another warden. Meanwhile I slept in the cupboard under the stairs, this being regarded as the most secure place in the event of the house being hit. My cousin Joan Marchant, who had celebrated her 21st Birthday at Ewell in May 1940, continued to live at No.9 and travel up to the City every day until her branch of the Bank of England was evacuated to Whitchurch in Hampshire. One night I was woken by explosions. A "stick" of three bombs had fallen across the village, bracketing Post 25. The first bomb hit a house at the corner of Lyncroft Gardens less than 100 yards from the post. My father and his colleague rushed to the spot to find a heap of rubble. But they heard voices calling for help, and started to dig through the wreckage. They found both the occupants alive. Hearing the whistle of the approaching bomb they had dived under their baby grand piano. This saved them. The second bomb hit cottages in the village High Street, even closer to the post; this is now the site of the local supermarket. The third bomb in the stick dropped on open ground near Ewell East station. Long afterwards a warden who was in Post 25 with my mother when the bombs fell told me that as the post shook and the lights flickered he heard her give an anguished cry. "Are you alright ?" he asked. "No" was the reply, "Those blasted Huns have made me drop a stitch". Another night our road was liberally spattered with small incendiary bombs, but no house was hit. I looked out to see one burning at the bottom of our garden by the Lanes Prince Albert apple tree, and another just over the fence in No 11's garden. As I went out, our neighbour from No.5, Roy Richards, a schoolmaster, came vaulting over the chestnut paling fences dividing the gardens, and attacked the bombs with a spade. I kept the tail fin of "our" bomb as a souvenir, but I no longer have it; no doubt my mother threw it away. Later the Germans added an explosive charge to their incendiary bombs, and hitting them with a spade was NOT recommended. In fact, the only damage our house sustained during the Blitz besides

broken tiles from falling fragments of anti-aircraft shells was when

the nose cap of a shell came through the bathroom roof. But in 1944

part of the front dining room window was sucked out by blast from German

V1 flying bomb which fell on our local brickfields, now a shopping centre/

industrial estate. School One day a boy brought a portable clockwork gramophone with him to the shelter. While the master was away he played a record of the Jazz drummer, Gene Krupa, making a "drum break" (an improvised solo). The master returned; "Stop that dreadful noise, boy !". The needle was lifted from the record. From outside came the sound of anti-aircraft fire and distant bombing. "That's even worse" said the master, "Carry on playing the record". In 1941 I sat the School Certificate examination, roughly equivalent to today's GCSE. If the sirens sounded we were to go to our shelters, but we were put on our honour not to discuss the paper between ourselves, or refer to any books. In the event, none of my papers was interrupted by enemy action. I managed to get the required five credits (two of which had to be in English and Maths) to gain exemption from Matriculation, the basic entry standard for a university in those days. I got a "Very Good" in English and credits in Maths, Latin, French and Physics; but only a pass in German. My German teacher, Herr Doktor Wagner, a refugee from Nazi Germany, was very disappointed in me. But I was still allowed to take German and French as my sixth form subjects. After the School Certificate exams I went off to a School "Harvest Camp" at King's Somborne near Winchester. The idea was that we should help with the grain harvest. We were even shown how to drive a tractor. It used petrol to start the engine and then ran on paraffin (kerosene). Only one of my class had any success with it, but his father was a garage owner. But we were too early for the harvest that year, so much of the time was at camp spent in rather boring weeding and clearing jobs. I was never very keen on sports at School, but I played Rugby and Cricket. During the winter of 40/41 we had to scour the pitch before the game looking for pieces of shrapnel which might cause injury if someone fell on them. After getting my nose broken by contact with an opposing player's boot, I took the opportunity to change to Rowing, a new sport so far as King's was concerned, and an all-the-year-round one. We rowed from the Thames Rowing Club at Putney. I soon graduated to an Eight, and earned my Rowing Colours when we beat U.C.S. Military Training Our "bible" was "Infantry Section Leading 1938". An exercise during our 1938 Field Day (which took place on Headley Heath), when were issued with blank ammunition (only 5 rounds, mind you) showed how antiquated were the tactics we were taught. While marching along a road were halted to "repel an enemy aircraft attacking from behind the column". Far from scattering and taking over, we had to turn about, raise our rifles to our shoulders at an angle of 60 degrees, and wait for the order to "fire" which was given when the officer judged the plane would be likely to fly into the hail of bullets. How futile such tactics would be against military aircraft had already been proved in the Spanish Civil War. As soon as I could I transferred to the Signals Platoon. Both my father and my godfather, Peter Curram, had been Yeomen of Signals at the end of the 14-18 war, and I was already familiar with the Morse Code and Semaphore. At first our only equipment besides flags was WW1 field telephones. These required a reel of wire to be laid along the ground, and many miles I covered on Wimbledon Common in this way. The "return" was through the earth via metal pegs, and we soon found that communication was easier when the ground was wet. Then in 1941 we got our first field radio, a heavy beast called the No.8 that required a lot of strength to lug around on one's back while the operator attempted, often vainly, to make contact with the other station. Naval Training Royal Inspection On another occasion the "Steadfast" unit formed the Guard of Honour outside the Mansion House in the City of London for King Haakon of Norway. My father commanded that guard, as well as one for King Peter of Yugoslavia on Derry & Toms Roof Garden in Kensington. Dartmouth At the time there was a flotilla of MGB's (Motor Gun Boats) based in Dartmouth under the command of Lieut.Commander Robert Hichens DSO DSC RNVR, a yachtsman who became one of the most successful of small ship commanders. Hichens and his officers were staying at the College. One evening I was in the town when a loud-speaker van went round recalling all MGB crews to their boats. From every pub sailors emerged, running to the waterside. Hichens and his officers, who had been having quite a party in the College wardroom, arrived in any vehicle they could find or commandeer. Rumour had it that German E-boats (motor torpedo boats) had been spotted in Lyme Bay. I watched, fascinated, as the gunboats' powerful engines roared into life, and boat after boat surged out of the harbour at a speed that left any vessel at a mooring rocking for long after under the influence of the powerful wash. They were back early the next morning. My father met Hichens on the way in to breakfast; "How did it go?" he asked. "Missed them in Lyme Bay" said Hichens, "so we went across and sat outside Cherbourg with our engines off. Caught them with their pants down at first light. Sunk one and damaged a couple of others". Hichens had correctly guessed the E-boats home port, and had acted accordingly. His death in April 1943 from what was literally the last shot fired as an action was broken off was a sad loss. Navigation School Oxford Just above us in Meadow Buildings were the rooms of Lord Cherwell (Professor Linderman) the Scientific Adviser to the Prime Minister. On one occasion we were having a party in our rooms when his butler appeared. "Lord Cherwell's compliments, gentlemen, and will you kindly make less noise. He is trying to work". We offered our apologies, and shut up. The only cause for complaint was the awful food. One evening the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke, dined at High Table. I remember hoping that he was getting something better than the greasy Welsh Rarebit that was our lot. H.M.S.Ganges Thanks to my earlier training with the Kingston Sea Cadets, after a test by Ganges Instructors, I was allowed to take charge of a 32 ft. cutter under sail, with a crew of up to 20, most of whom were no more than ballast. Sailing in a stiff breeze in the estuaries of the Stour and Orwell could certainly be invigorating. H.M.S.Corinthian We did lots of practice, but the gun was only fired "in anger" once. I was sleeping in my hammock slung between stanchions on the messdeck when "Action Stations" sounded. An unidentified ship had been sighted. The "galley wireless", that source of all rumour aboard a ship, reckoned that it was the big German Cruiser "Hipper". Having cleared the gun for action we were ordered to load with star shell, the object being for the shell to explode in the air beyond the target, so silhouetting it. "Bearing Red 130"; the trainer (No.2) turned the gun on to that bearing. "Range 030 (=3000 yards)". "Sights moving" said the layer (No.1), "Sights set". We covered our ears. "Fire" was the order, and No.1 punched the trigger. This was the first time we had used a full charge, and the shock of the recoil was very marked. The shell burst in the air as scheduled. Alas, the range was too short, and it revealed nothing. However, it did produce some frantic signalling from the target; it was one of our ships. It's just as well it wasn't the Hipper......... But the Battle of May Island, as it was facetiously known, did produce some casualties. Beneath the gun platform were the "heads" (toilets). The shock of the full charge shattered most of the toilet bowls, and buckets were much in demand. "Defaulters" Next morning I appeared as a "Defaulter" before the Commander.

The Master-at-Arms called my name. "Off Cap" (Defaulters had

to remove their H.M.S King Alfred Posted to the Mediterranean Naples When officer of the watch in the Naval Headquarters in Naples, H.M.S.Byrsa, I had my first introduction to the problems caused by drunkeness. I was called down to the vestibule to remand to the cells a sailor who was, quite literally, fighting drunk, and had been picked up by a shore patrol. He was disinclined to participate in the short formal proceedings and made a dive at me. I side-stepped, and his escorts grabbed him and wrestled him to the floor. His arms were handcuffed behind him, and he was then hauled to his feet, swearing loudly and incoherently. The Petty Officer read the charges, at the end of which I remanded the drunken sailor to the cells. As he was dragged away, the Petty Officer remarked "I wouldn't like to have his head in the morning". While in Naples I paid a visit to Pompeii, which impressed me tremendously. It wasn't just the magnificence of the city and its houses but little things like the ruts made in the streets by the passage of chariots and carts up to that day in AD 79 when Pompeii was destroyed by molten lava from Vesuvius. Greece BYMS 2075 Mines and minesweeping To tackle the magnetic mine a LL sweep was used. This consisted of a long floating double electric cable towed astern, one of the cables being longer than the other. At the end of each part of the cable there was a copper electrode. Down the cable was passed a strong electrical pulse, creating a powerful magnetic field to detonate the mine which, hopefully, had been not been disturbed by the weak field of the wooden hull of the minesweeper passing over it. For the acoustic mine a water-tight steel casing containing a diaphragm and an electric hammer was lowered over the side, projecting its sound ahead of the minesweeper with the aim of detonating the mine before the ship reached it. To make them more difficult to detect, the Germans fitted their magnetic and acoustic mines with 80 day clocks and delay timing mechanisms which could (a) delay the time between the mine being laid and it becoming live and (b) allow it to be activated by up to 14 ships before exploding as the 15th passed over it. This meant that we could never be sure that an area of sea was free of magnetic and/or acoustic mines until we had swept the area 15 times which could be tedious. A point to note is that it was only after the cessation of hostilities that the minesweepers did their most intensive work. During the war their main job was to keep open swept channels. It was only after the fighting stopped that they began to clear minefields. The ship's equipment The ship had twin screws driven by two 500 hp General Motors diesels. Another 500 h.p. diesel was used to provide power for the LL sweep. There were also two 250 h.p. diesels to provide electric power for the ship's services; cooking was by an electric stove. The main armament was a 3" gun (roughly equivalent to the British 12 pdr.) on the foc'sle. Either side of the bridge superstructure were 20 mm. Oerlikon cannons. There were mountings for Lewis guns either side on the main deck just aft of the superstructure. Immediately below the bridge was the wheelhouse, with the chart and radio rooms. Below them again was a small wardroom and the officers cabins; a single cabin for the skipper on the starboard side, and one with two berths on the port side. The officers' needs were looked after by a Steward; in the later stages of my service aboard 2075 we were the envy of the rest of the flotilla because our steward had formerly been the personal valet to the Duke of Alva. He really had style......... The galley was immediately for'ard of the wardroom, with the mess deck beyond that. Bob Davidson South to Crete Crete We joined a flotilla made up of two British and six Greek YMS. The Senior Naval Officer was a Commander R.N.R., who had a flotilla of Isles class trawlers, which had been designed so that they could revert to fishing work after the war. They were steam driven and, unlike our diesels which could be started at the push of a button, needed time to raise sufficient head of steam in their boilers before getting under way. The SNO forgot we were different. One day, as we were sitting round in the wardroom of the other British YMS over drinks, a signal was brought to the skipper who commanded the mixed British/Greek flotilla. "Raise steam for 10 knots" it ordered. The skipper grinned, and called for a signal pad. "Your signal acknowledged. Request boiler and thirty tons of coal". There was no reply. We spent more than a month sweeping the waters off Heraklion, with only limited success. That there were mines around was clear from the Greek caiques who occasionally snagged one in their nets. They hated to waste the explosives contained in the mine, but it was a dangerous business to dismantle it; one mistake and the caique became indistinguishable from drift wood. One night there was a report that German R boats (gun boats) had left Suda Bay heading for Heraklion. Fast asleep in my bunk I dreamed that Bob came into the cabin and left me a .45 revolver, saying "R boats are out and may attack the harbour". I woke up in the morning to find that I was lying on a .45 revolver. The report of how I had turned over and gone to sleep again when told that R boats were out gained me a quite unwarranted reputation for coolness. Rhodes That same night our flotilla was ordered to Rhodes to sweep a channel into the port before British troops landed. Rhodes is the largest of the Dodecanese islands. Italian since 1912, these islands had been occupied by the British in 1943 when the Italians surrendered. This didn't suit Hitler, and he withdrew paratroops from the Russian front to retake them ¬which they did. The German troops there had not been defeated, and their morale was therefore high, despite being cut off from home by Allied advances in Italy and Greece. We were only there a short while, but during this time I met a young Army officer. I was with him when he carried out a search of the office of the German General commanding. In the desk were some unissued Iron Crosses 2nd Class; I was solemnly awarded one ! The officer had another assignment, which was to check bridges and culverts on the island. I accompanied him in a military VW, a sort of jeep on the basic VW chassis. We had a German soldier as chauffeur. Somewhere in the archives of the old War Office there are photos of me standing under bridges and by culverts, simply for scale purposes. The German driver (wearing Afrika Corps uniform) was very formal, and when we left him he clicked his heels and gave a smart salute. Leaving Rhodes we called at the island of Symi after an abortive attempt to carry out some naval manoeuvres. We were in two columns, each British ship leading three Greek ships. At the flag signal "White 9" the leading ships were supposed to turn together to starboard, the remainder in succession, thus forming one single line. The leading ships turned together, but the Greeks got into a lovely tangle, some even turning the wrong way. Our flotilla commander gave up, and we went into the small harbour. Here we found some very welcome flour and fresh fruit in a store guarded by an Indian soldier from the newly arrived garrison. He wasn't at all sure he ought to let us have the food, but the lads so confused him that he must have decided that resistance was useless. Our need for fresh fruit was, however, quite genuine. Our Chief Engineer actually got scurvy, which excited the doctors no end. They wanted to keep him as a prize exhibit, but he wasn't having it. Kos As soon as the gang plank was down a German marched aboard, apparently seeking orders. So far as we were concerned the sensible thing was for them to carry on with what they were obviously doing, policing the place. Saluting smartly, he marched off again. Indeed, the local Greeks regarded their real enemy as the Italians. Fed up with their erstwhile allies, the Germans had already interned them. Somewhat later the Army, in the shape of an Indian regiment from the State of Alwa, arrived, having been landed at the wrong place. When they marched the Italians (now technically our allies) to waiting Landing Ships for evacuation, they had to protect them from the local population. Being the first British ship to arrive, we were hailed as liberators. Small children were led forward to present us with large bouquets of multi-coloured flowers, and a choir of girls in national costume sang to us from the quayside. The flour we had hi-jacked in Symi made us very popular in Kos. They had a first class baker, but no flour. A deal was soon negotiated. They got the flour and we got free fresh baked bread. The baker spoke English, albeit with a strong American accent, having worked for some years in Chicago. Many willing hands hauled the flour sacks out of our sweeping store, and carried them in a triumphal procession across the square to the bakery. There was only one incident to mar our short stay at Kos. In the clear water of the harbour our anchor chain could be seen lying across what appeared to be a large packing case. Having heard some rumours about home made German magnetic mines consisting of explosives in a block of concrete that was disguised with a wooden exterior we consulted a Naval explosives expert who happened along. He took one look over the bow, and said "Oh dear". He got his diving gear and went down to have a look. "You're lucky" he said "it isn't armed". My Army friend turned up again, and took me for a ride round the Island on the back of a motor-cycle. In the course of this I saw the tree under which the great physician Hippocrates was said to have taught. I only just got back to the ship in time, an unexpected order to sail at once having been received. Bodrum We were visited by a British Army officer who was the Liaison Officer to the Turkish XXVth Army. All the officers of the flotilla, British and Greek, were bidden to a party that evening to be given by the General commanding. Our Liaison Officer gave us some very good advice. "Before you go ashore" said he, "drink a tin of condensed milk each. It'll provide a lining to the stomach." The party was given that evening in the open air not far from the town. We all sat at a long, low table, Turks, Greeks and British intermingled. The Liaison Officer, who could speak Turkish, sat on the right of the General. There was only one drink, raki, which is an aniseed flavoured spirit akin to the Greek ouzo or the French pernod. There was a long succession of toasts, at each of which we were expected to down in one a small glass of neat raki. Water was provided to extinguish the internal fires. We ate a variety of sweetmeats. As the party progressed, and tongues were loosened by the alcohol, a quarrel broke out further down the table. In 1922 the Turks had massacred thousands of Greeks at Smyrna (renamed Izmir by the victors). Someone, whether Greek or Turk I wouldn't know, was tactless enough to bring up the subject, and tempers were rising. The British Liaison Officer came to the rescue with a Verys pistol (a device for firing a coloured signal flare). How it came about he had one with him is a mystery ; perhaps he foresaw the need for creating a diversion. Pointing the pistol over the sea, he fired a flare, and then another one. The General decided to fire the pistol himself. Careless of where he was pointing it, he fired a flare inland. This landed on a thatched house in a nearby village, the roof of which promptly burst into flames. Not one wit discomposed the General clapped his hands and gave an order. Shortly afterwards a platoon of Turkish troops doubled down the road to the village. They had no fire-fighting equipment, but they promptly set about pulling down the house. Pleased with himself for saving the village, the General continued with the party. Nobody seemed to care about the unfortunates who had lost their house. But at least the quarrel between the Greeks and the Turks was forgotten. Leros Anyway, we survived the operation without any casualties. One of our seamen, however, went sick with a fever and a very sore throat. One thing the Americans had provided with the ship was a very good Medical Manual. Bob and I studied it and came to the conclusion that he could well have diptheria. The only doctor available was a German Naval Surgeon who came aboard and confirmed the diagnosis. He spoke very little English, and the German I had learned at school came in useful, even if my vocabulary tended to be rather too literary for the circumstances. Shortly afterwards our seaman was taken ashore and driven to hospital in a German ambulance. He recovered, and we picked him up on our way to Alexandria some weeks later. But 2075 was placed in isolation, and we spent a week moored to a large buoy in Porto Largo harbour, forbidden to have contact with anyone else. We ran out of rum - in those days the Navy still issued every seaman with a daily tot of rum at noon, diluted with two parts of water, thus making it "grog", so named after Admiral Vernon, famous for the taking of Portobello in 1739, who introduced it in 1740 to combat the drunkeness that was rife in the Navy of those days, and who was known as "Old Grog" because he habitually wore a Grogram sea cloak, a material made of silk and mohair. A British destroyer duly sent a jar, but its boat wouldn't come alongside. Instead the jar was placed on the large buoy to which our stern was moored by a boats crew all wearing medical face masks. This caused much hilarity among our lads, who gave the unfortunates in the destroyer's boat crew a very rough time. However, our leisure wasn't wasted because in a hut on an isolated shore we found a large supply of Italian hand grenades. These were used for fishing, which made a welcome variation from our normal diet of tinned food. Just across from us was a sad reminder of the war, the burned out wreck of a British Yard Minesweeper, almost identical to our own 2075. This had been caught in Leros harbour when the German paratroops landed in 1943, and set on fire before it could escape through the narrow entrance. Kalimnos and Khios On our way north we passed between several rocky islands with high cliffs, rather like those in the film "Guns of Navarone". In clear weather one afternoon Bob gave me permission to leave the Coxswain on the bridge and come down to tea in the wardroom. After a while there was a call from the Coxswain asking me to return to the bridge. We were heading straight for a sheer cliff face, yet the gyro compass was showing the course I had given him. I took one look and gave the order to steer by the magnetic compass. We came back on to a safe course again. What had happened was that the gyro compass had suddenly slipped 60 degs, and the helmsman had simply followed it round. Thank goodness it hadn't happened at night. Izmir (Smyrna) But the Turkish authorities kept a close eye on us. Ashore one day , Bob and I were followed everywhere by a member of their Secret Police. Bob had already experienced this in Istanbul. After a while he walked up to the man, smiled, and asked him "Is the Secret Police very busy these days ?". Somewhat embarrassed, the man, who understood English, made a non-committal reply, and retired. But he still kept us in sight. A meal ashore attended by all the British officers on the last night we were there ended in a memorable fashion with us driving back to the ship in two open horse drawn carriages, the drivers of which were encouraged by financial incentives to race. I've forgotten who won, but we were pursued by the sound of Turkish police whistles. Samos Alexandria Our engines were stripped down and reassembled, and we went out for engine trials. Coming back into the dock we had to turn short round to get to our berth. Immediately behind us was a troopship full of men who had been years in the Middle East, waiting to sail to England. Bob ordered "stop port, hard a port". 2075 swung to port pointing directly at the troopship. "Slow astern port" said Bob. But when the engineers attempted to put the port engine astern it promptly stalled. Bob did exactly the right thing; "Midships. Half astern starboard". The starboard engine promptly emulated its companion. We were helpless, heading slowly but remorselessly straight at the side of the troopship. Everyone was paralysed, except Seaman Burgess, a farm labourer from Cheshire, not famed for his quickness of thought. "Us is a-going to hit 'er" he said and, picking up a coir fender he shambled forward and hung it hopefully over the bow; others followed his example. Seeing what was happening, the troops who had been looking out of portholes and over the rail scattered. With a rending crunch 2075's stem hit the side of the troopship, pushing in several plates, fortunately well above the larger vessel's waterline. Save for some scraped paintwork, our only damage was the total destruction of the fender Seamen Burgess had interposed between the two ships; rising to his feet he looked really comical as he ruefully held up the rope lanyard that was all that remained. Bob later went aboard the troopship to apologise to the Captain, who was very understanding. His passengers weren't so pleased as their departure for England had to be delayed while the buckled side plates were replaced. Our Chief called the dockyard engineers some very rude names, and the problem was soon rectified. 2075 had a small boat. After being used only occasionally and being

exposed for some years to the Mediterranean sun while it sat on its

cradle, it could hardly regarded as seaworthy any longer. I indented

on the Dockyard stores for a new one, having already seen there a lovely

varnished 14ft sailing dinghy. My request was rejected out of hand.

I returned to 2075 and reported failure. It was suggested that I try

bribery. The Stores official was invited on board for drinks, and when

he left he was carrying a bottle of duty free gin. We got our lovely

varnished sailing dinghy the next day. Salonika One of our Motor Launches, ML1226, that had worked with us in the Dodecanese, was lost. She hit a mine and was reduced to matchwood. There were few survivors. These vessels were very useful for mine destruction duties i.e. destroying by gunfire mines that had been cut to the surface. But on one occasion we got called out to assist the Fleet Sweepers with mine destruction, they having cut so many to the surface that they couldn't cope themselves. We spent seven hours firing at mines that day, with everyone taking their turn. The rifles got so hot that gloves were worn ! The Fleet Sweepers proved "chummy" ships. I remember one night when we took out their mail to them, and anchored near them. We were invited on board one ship to see a film, shown on the sweep-deck in the open air. Afterwards we had drinks in the wardroom before being taken back to 2075 in their "skimming dish", a small but fast motor boat. We worked hard for several weeks, with some success. A photographer's shop in the town had in its window a picture of 2075 at work, silhouetted by the sun, with a magnetic mine exploding just astern of it. I got a copy and sent it home, but it never reached Ewell. Between times I managed to get in some sailing in our brand new dinghy. One Saturday afternoon while we were berthed alongside the quay with several trots of Greek caiques (wooden fishing and general purpose boats) moored astern of us we received a signal that one of the Fleet Sweepers was coming in with a badly injured man whose arm had been caught in a winch. I called together some of our crew and set about clearing a berth for the Fleet Sweeper. The occupants of the caiques either couldn't, or didn't want to hear, my plea for them to move. The Fleet Sweeper was now approaching and there was an ambulance waiting. So I told my lads to cast off the caiques' mooring lines so that the wind would push them away from the quay. Some very unhappy Greeks emerged from below to find they were drifting across the harbour. We took the Fleet Sweeper's lines, and the casualty was landed. The Captain lent over the bridge and asked my name and ship. Later he sent a formal message of thanks for my initiative in clearing the caiques from the berth. But it was too late to save his crew member's arm. We had our excitements. One night the Chief was knifed by a sailor from an American Liberty ship as he left a bar and had to spent some time in hospital before rejoining the ship. Then our operations in the Gulf came to a sudden end. A mine exploded too close for comfort, started a leak in the hull and, as we subsequently discovered, shifted the port engine on its mountings, with disastrous effects on the bearings. With pumps going we limped back to Salonika. It was clear that a major overhaul was needed and we were ordered to Piraeus. Thanks to being a wooden ship the planking in the hull "took up", and after a while the pumps were no longer needed. But we only had one engine. Our departure from Salonika was not without incident. On the morning we were due to sail Seaman Jeremy Bentham was missing. I asked the crew if they knew where he was. They were naturally reluctant to "split" on him, but I pointed out that if he didn't sail with us he would find himself in a military prison, as he had already broken ship once. They told me where they had last seen him the previous night, at a bar in the town with a girl who worked there. Collecting a Military Policeman and a jeep, I went to the bar. The owner knew the MP and didn't want trouble. He told us where the girl lived, which was some five miles outside the town. We picked up an Interpreter and, when we got to the area, a Greek policeman as we were going to a civilian house. When they heard the address neither of the Greeks was at all keen on the idea, and the policeman armed himself with a rifle. It seemed that the place was a hotbed of ELAS (Communist guerrilla) supporters. We certainly didn't get any help from the local population, who were distinctly hostile. We were about to give up the search when I spotted a sailor's blue jean collar hanging on a washing line. The MP wanted to know if he should formally arrest Bentham. I didn't want that, as it meant we should have to leave him behind in Salonika, so I asked the MP to stay in the jeep. I knocked at the door of the small single storey house. There was no reply, so I pushed the door open with my foot. Inside was an old woman who started to scream at me. I slipped my hand into my pocket and brought out a small revolver, an Italian Biretta 7.65mm, which I had acquired during our week in isolation at Leros. I didn't point it at her, only held it in my open hand so that she could see it. Mumbling to herself, she stepped back, and I pushed past her. Sure enough, there was Seaman Bentham with the girl. Grinning sheepishly, he got dressed. The woman and the girl set up a great wailing. It seems they thought I was going to shoot Bentham. By now a hostile crowd, consisting mainly of women, had gathered, so we got out of the area as quickly as we could, followed by a shower of stones and abuse. To Piraeus Bob was taken to hospital, and sandfly fever was diagnosed. On George's recommendation, the Commander M/S awarded me a Naval Small Ships Watchkeeping Certificate, considerably earlier than I could have expected in the normal course. There was an Officers Club in Athens, a superb edifice built on the side of a hill. It had a marble staircase leading down from the entrance, with a landing half way. Somehow I got involved one night in a rugger scrum on the landing between New Zealanders and South Africans. I've forgotten whose side I was on, but I distinctly remember being heeled out and rolling down the lower flight of stairs to the cheers of the assembled company. Malta In Malta we moored to a buoy in Sliema Creek, which is just off Grand Harbour. The other officer left to return to his ship, and I took over command of 2075. After a few hectic days in Malta we were ordered to Messina in Sicily. A large ocean-going tug, the "Patroculus", was detailed to escort us. Outside Grand Harbour the tug signalled to ask what speed I could make. I told her 8 knots. "I'll pass you a tow" said she, "It'll be quicker". It was too; we set off at 13 knots, the fastest speed 2075 had ever achieved ! Messina When Bob Davidson finally got back to the ship, having hitched lifts from Piraeus and then from Malta, I was allowed some leave. Not far away was Taormina, where the San Domenico hotel had become a rest centre for officers. It was situated on a steep hillside south of Messina, with fabulous views over both sea and mountains. It's guest book was full of the names of the great and the good, including European royalty and film stars. But the signature that the Hotel seemed to value most was that of Henry Ford. One part of the hotel was out of use, it having been hit by a bomb or shell during the fighting in 1943. Looking through the ruins one day I saw something black through the rubble. Clearing away the debris I came across a boot. Above it was a black uniform of a German SS officer, and in the uniform a grinning skeleton. I told the hotel staff, but they weren't very interested. Evidently it wasn't the first. Also staying at the San Domenico was another Oxford friend of mine, Jimmy Bristow, who had been at Winchester. One day we went for a long walk, starting inland and heading towards Mount Etna from which a thin plume of smoke was rising. We met no-one for hours save an occasional goatherd. About mid-afternoon we came to a village, whose name was, I think,Granite. It was the hour of the "sonnellino" (=siesta), but as we walked down the main street curious faces peered out at us. We indicated that we would like to buy some oranges. Once our request was understood, we were conducted to a shed. When the door was opened, the place was piled from floor to ceiling with oranges, and we were told to help ourselves. Filling our shirts and pockets with fruit, we went on our way. We ended up on the coast again and took a train back to Taormina. It was one of those days that abides in the memory; we were young, fit and free, and life seemed very good. In Messina the engine repairs were proceeding apace. I did once go to a local dance to which British officers were invited. For a partner I was allocated a very pretty girl with, most unusually for that part of the world, red hair - perhaps a forbear was one of those Normans who ruled in Sicily in the 11th century. The only snag was that Mama had come too. While I danced with daughter, Mama scooped up as much of the food provided as she could into paper bags which she secreted about her ample person. Malta again Ashore in Sliema there was a "Wrennery", and there I looked up a Wren named Joyce who I had first met at Taormina, and with whom I had explored the famous "Blue Grotto", a cave that could only be approached from the sea. She showed me the sights of Malta, including a visit to St.Paul's Bay, the traditional site of St.Paul's ship-wreck. She was fun, but somewhat empty-headed. I had her to tea on board one afternoon, and made the mistake of detailing two members of the crew to row the dinghy. The only way to board 2075 from the dinghy was by a rope ladder slung over the side. As she clambered up I realised that the two seaman were able to see up her skirt, doubtless getting a fascinating glimpse of bare flesh above the stocking top, for there were no tights in those days. It was common enough in the old Navy for boat's crews to be ordered to keep their eyes IN the boat. I reversed this and told them "Keep your eyes OUT of the boat". Grinning broadly they obeyed. But it was all round the ship in a few minutes. After tea I rowed Joyce back to the shore myself. While we were in Malta we had to say goodbye to Seaman Jeremy Bentham. After the escapade at Salonika his leave had been stopped. Left virtually alone on board one day he decided that he needed a drink. So he used a saucepan in the galley to boil some boot polish, afterwards straining out the raw industrial alcohol thereby released. Not surprisingly, he became fighting drunk, and it took about half a dozen members of the crew to subdue him. Bob had enough, and Jeremy Bentham departed, taking his outsize hangover with him. But the Cook was NOT pleased at the state in which his saucepan and strainer had been left. Just before Xmas 1945 Bob Davidson left the ship, heading for England and demobilisation. Back home he visited Ewell, where he met my cousin Joan Marchant. A few years later they were married. My new skipper was another Bob, Lieut. Bob Powell. He was a very different character from his predecessor, being a thorough-going extrovert. But he was a good seaman, and had a lot of experience. The first peacetime Christmas for six years was well celebrated aboard 2075, and we held a short service on the mess deck at which I read the lesson. The main item on the menu was Roast Pork, which came from a pig named Percy that 2075 had acquired in Salonika. It had been well looked after by Seaman Burgess (the farm labourer from Cheshire), and he had supervised the slaughter and hanging. Peter Guinness Up the Adriatic Trieste The political situation at Trieste was not a happy one. The year before Tito's forces had got into the town before the British. This didn't suit the Allies, who were determined that Italy (our allies since their surrender in 1943) should control the port, and not a Communist state. After a confrontation in which the British Commander made it clear to Tito that he would take the town by superior force if need be, the area around Trieste was divided into two zones, Zone A (Italian), which included the town, was occupied by British forces, while the less populous Zone B was allocated to the Yugoslavs. From our berth on what was the fourth side of the Gran Piazza we witnessed a large demonstration by Communist supporters of Tito designed to take over the town. Forewarned, the authorities had fenced our quayside off with barbed wire, and had one platoon of every company of British troops standing by in case riots broke out. We issued the crew with small arms, which were to be kept out of sight, and only used in the event that the demonstrators broke through the wire and attacked the ships. It was an ugly situation, but saved but what I can only describe as an old fashioned cavalry charge by mounted Italian Carabineri. They had formed up in a side street, and at a word of command, they tore into the crowd at the gallop with batons waving. The mob evaporated. On another occasion I accompanied our flotilla commander, Lieut.Commander Bob Viner, to the port of Pola to meet the British Naval Liaison Officer there. This involved passing through Zone B occupied by Tito's Serbs.We had no trouble on the outward journey, but on our way back we turned off the main road for what appeared to be a short cut. When we came to the border between the two zones we got a distinctly unfriendly reception at the Yugoslav post. After an argument in Italian (one of our party spoke it fluently) with what appeared to be a very junior private, we demanded to see his officer "Dove il vostro ufficiale ?". Indignantly he replied "Io" (= that's me). That did it. He turned out the guard, some of whom were armed with sub-machine guns, and drew his own revolver. Even though we could see the British sentry a few yards down the road, we had to turn round and go all the way back to the main road. And then we were questioned again at the crossing point as to why we had turned off on to the side road. All in all, our relations with the Yugoslavs at that time were not of the friendliest. When we were working close inshore off Zone B we came under fire. A formal protest to the Yugoslav authorities brought the explanation that they were only indulging in target practice and we must have got in the way. We had our own back, however. The next time we swept some mines to the surface off that part of the coast, we made sure that they were between us and the shore. We opened fire on the mines enthusiastically. A subsequent protest from the Yugoslavs enabled us to say, with absolute truth, that we were firing to destroy mines, an action which could only be in their interests. After that a truce broke out. German measles Minesweeping off Trieste One day, after we had parted sweeps three times on obstructors, we got a mine caught round the otter, the steel vanes supported by the Oropesa float that kept the wire towing out on the ship's quarter. Bob Powell headed for shallow water in the hope that the mine would then break surface. It didn't, so after the sweep wire had been cut, I went out in the dinghy with two seamen at the oars. Using a bucket with its bottom knocked out I tried to see if the mine was still caught round the otter under the float. At that moment another of our ships that had got a similar problem managed to detonate her mine, and the water was promptly so muddied that I couldn't see a thing. Bob then showed what an experienced officer he was, doing something that never appeared in any instruction manual. He passed me a line which I secured to the float. Leaving the dinghy to fend for itself, he then set off at high speed, causing the otter to surface eventually and release its ugly looking passenger. While 2075 was engaged in destroying the mine, we drifted in the dinghy until we were picked up and taken in tow by a Motor Launch, the skipper of which flatly refused my admittedly frivolous request for the three of us to be issued with a tot of rum as "survivors". Another day something got caught in the sweep, causing the Oropesa

float over the otter to behave in a peculiar manner. It was clear from

the tension on the wire that whatever was in the sweep was heavy. If

this went on, there was the risk that the sweep wire would break. If

that happened on deck, it could cut a man in half. To ease the strain

on the wire I asked for "dead slow". The sweep Various solutions were proposed to the problem of chain moorings. One was to incorporate a section of the Mark 1 wire the Fleet Sweepers used to cut the obstruction before it destroyed our sweep. But the device we adopted was to fit explosive cutters at intervals on our sweep wire. On the first occasion we used them we cut two mines with chain moorings without losing any spread or affecting the sweep in any way. But they could cause difficulties. That same afternoon, while running at slow speed through swept waters, we were surprised to see the float go under and drop right astern. We dropped out of line, and hauled the sweep. As usual on such occasions I cleared the sweepdeck (except for the winchman) and called everyone up from below - just in case anything untoward happened. The sweep was hauled in slowly. I was looking over the stern watching for the otter to appear when I saw a large brown mass coming up on the sweep. Looking closely at it I decided that it couldn't be a mine, so I ordered it to be hauled close up. It proved to be a mine-sinker, complete with wire and all its fittings. This was obviously a desirable acquisition because it would establish how the mines had been moored. But when it was clear of the water we discovered to our horror that the wire was resting in the jaws of an explosive cutter. If the cutter went off we would loose the whole issue. Bob came aft and took charge. I was lowered over the stern and managed to render the cutter harmless by interposing a piece of metal between the striker and the detonator. Then a chain sling was passed down to me and I was able to shackle this on to pair of lifting eyes. The weight was taken off the sweep by another pennant, and we went back into to Trieste with the mine sinker hanging over our stern. A crane was subsequently sent to remove it. The Commander M/S was delighted to have it, and ordered "2075" to be painted on it. He recommended me for accelerated promotion to Lieutenant, but that assumed I was still in the Navy at the earliest possible age, twenty-one and a half. "Big Ships" The cruiser HMS Liverpool was one such visitor. To make room for her, I shifted 2075 and the other ship in the trot out of the way with hardly anyone on deck. Moving two vessels secured to each other was a common enough practice in our flotilla, and I though nothing of it. As the Liverpool, its decks awash with crew most of whom had nothing to do, slid by I noticed an officer on the wing of the bridge staring at me. It was Lieut.Commander Henry De Vere Barnes R.N., who had been my Divisional Officer at HMS King Alfred, and who was now First Lieutenant of the cruiser. I think he recognised me, but I don't think he approved of the very casual attitude adopted in small ships. Another time we had the cruisers H.M.S.Orion and H.M.S. Superb. The former berthed in the port, and the latter anchored outside. It was no coincidence that their visit co-incided with May Day, the big Communist Festival, when trouble was expected. We were invited aboard the Orion for drinks in the wardroom. Rear Admiral Killahan, flying his flag in Orion, expressed an interest in seeing minesweeepers at work, so he and some of his officers were invited to join us for a day's "hunting". Knowing that some R.N. officers had a low opinion of minesweeping, our Flotilla commander made sure that they would be impressed by choosing an area in which we knew from a wartime Italian chart that there was a field of moored mines. Sure enough, they were there, and we soon had 15 mines bobbing on the surface. After we had hauled sweeps we returned to dispose of them by gun fire. That day 2075 used 2000 Oerlikon cannon shells, 4000 rounds of .303 ammunition, and 300 rounds of .5 anti-tank bullets. There were some spectacular explosions when a horn containing a detonator was hit. Some mines wouldn't explode although the casing was peppered with holes. Our practice with these was to run past them at full speed so that our wash filled the casing, causing the mine to sink to the bottom. The R.N. officers thoroughly enjoyed their day out with us, and freely admitted to having revised their opinion of our trade. An incompetent skipper He claimed minesweeping experience but quickly showed his lack of it. One day the ship ahead of us brought to the surface the mast and part of the hull of a wrecked fishing boat. Then we got a mine caught round the otter, and proceeded to drag it through the wreckage. There was a good chance the mine would explode, so I got everyone upon from below, just in case. It didn't, nor did the mine appear when we got into shallow water. So had we lost the mine in the wreckage, and picked up something else ? The only way to find out was to haul the sweep in while going slow ahead, and look. So I cleared the sweep deck except for the winchman, and hauled in gently until the otter was visible. At first I could see nothing. Then looking down, I saw the mine only a few feet from the stern. At that moment "Boy Blue" called down from the bridge suggesting he should stop engines. This would have had the effect of allowing the mine to catch up with the ship. My response was not couched in terms in which a superior officer ought to be addressed. I had the sweep veered very gently, and cut when the mine was at a safe distance. It wasn't until the Commander M/S explained to him what would have happened if the engines had been stopped that "Boy Blue" ceased threatening to log me for calling him a "b..... fool". The affair ended with apologies, but it didn't enhance his reputation, particularly with 2075's crew. Venice After a while, if we had been pleased the Commander Minesweeping, we were allowed to take our ships over to Venice for the weekend, mooring up in the Grand Canal just by the Danielli Hotel. It was a blissful time, but not without its problems because the crew did tend to get drunk. One of our seamen, a Liverpudlian named Stevie Allen, came aboard so drunk that I had to charge him. It wasn't easy because Stevie was in a very happy state, and kept trying to put his arms around me, saying that I was a fine fellow, and wasn't the skipper a so-and-so. Finally he fell flat on his face and got carried below. My application to join the Colonial Service Arrangements were made for me to fly, but these broke down because some very unseasonal rain reduced the airfields in Northern Italy to quagmires. There was nothing for it but to cross over into Austria and go by train. I hitched a lift in the back of a 15 cwt truck. At the Italian/Austrian border the post was manned by a Guards Regiment. The astonishment of the Lance-Corporal who drew aside the canvas covering the back of the truck on finding that it contained a Naval Officer had to be seen to be believed. Collecting himself he saluted smartly and said "Sorry, Sah". The driver remarked to his mate "We should carry a sailor every time. Don't half make the border crossing easier". Crossing Europe by train At Dover, being the only representative of the senior service, I was first off the cross channel steamer. I got a taxi to Priory station and found a London train just about to depart. I walked into my father's office in the Midland Bank Head Office just in time to cadge lunch off him in the Managers' dining room. While I was home my 21st birthday was celebrated. I was in Trieste on the actual day, but I said nothing about it because I would have been expected to throw a party. And I knew what that could involve...... Back to Trieste Home again Holland My skipper was Lieut. Ricketts, who was commonly called "Red", because of a flaming mop of hair of that colour. Although fairly new to minesweeping, he was a good seaman. But having served most of the time with professional Royal Navy officers, he adopted their approach, and left all the ship's work to me as his First Lieutenant. The advantage was that he didn't interfere with me; the disadvantage was that he didn't help with any of the administrative work. 2230 had a very complicated system of victualling accounts that was quite new to me. My plight would have been even worse had not the Jewish "Bunts" (Signalman) been an accountant in civilian life. I think he must have been the inventor of what is now known as "creative accounting". Red's one failing was a colossal appetite for alcohol, his favourite drink being Guinness and Champagne, known as "Black Velvet". We once tried Dutch Advocaat and champagne, naming it "Yellow Peril", but it didn't catch on ¬perhaps just as well ! Red didn't drink at sea, but out came the bottles as soon as we berthed. He had been a submariner in the Mediterranean. His skipper was Ben Bryant V.C. to whom the whole crew was devoted. Just before setting out on an operation from Malta in 1943 they had a party aboard an American Navy ship. The American Navy was, and is, "dry", so the British provided Rum and the Americans the Coca-Cola. One of the problems about "rum and coke" is that the sugary soft drink tends to conceal the amount of rum consumed. On his way back to the submarine Red fell down a ladder and broke his arm. He was landed, and the sub. sailed without him. It never came back, being lost with all hands. "Red" had never recovered from the tragedy, and started drinking heavily. Sweeping off the Friesian Islands Thanks to its powerful engines and twin screws, 2230 had little difficulty in manoeuvring to moor in the confined waters of the harbour at Terschelling, even with a strong tide running. But we had some single screw Motor Minesweepers working with us. The reversing gear for their engine was operated by compressed air stored in cylinders, known as "bottles". It was worth watching them come in to moor. An inexperienced skipper could go from ahead to astern so many times that the compressed air became exhausted, and the engine was stuck in whatever gear it had last been shifted into. All he could do was to anchor (if he hadn't already run aground or rammed the quay), and wait for the bottles to be recharged. But we weren't working all the time. The day after I joined 2230 we took her up the Ship Canal to Amsterdam and moored in the extensive docks. I liked Amsterdam as a city, and we had many enjoyable outings there. While 2230 was back in Ijmuiden having a defective generator repaired, Red and I visited Alkmaar, where I restocked the ship's library with thrillers published by American Pocket books; one afternoon we sat on the beach at Bergen-am-Zee eating cherries. It was in Ijmuiden that I received a letter telling me that I had been selected for the Colonial Administrative Service, and earmarked for the Gold Coast. Operational again, we returned to work between Terschelling and Borkum. Our routine was interrupted once by a request from Trinity House to check that an area in which they wished to re-lay an important buoy was clear of mines. Having done the job, we anchored, but then had to take shelter in Borkum when a westerly gale blew. From Borkum we went to Delfzijl, a delightful town on the Dutch side of the river. One evening we drove into Gronigen, the provincial capital, which is about 30 km from Delfzijl. I was interested to see the place, because I knew that it was where my father had been interned after the 1914 Antwerp debacle until his escape the next year. We had a splendid dinner there and went on to a dance. My partner was a very pretty girl, but communication was difficult as she couldn't speak English and I couldn't speak Dutch. It was while we were heading out to sea that a signal came through

confirming my "Class B" release at the request of the Colonial

Office i.e. I was to be demobilised as soon as I could be replaced because

I was wanted for other work. This happened to coincide with an Admiralty

decision that 2230 and the other British YMS could no longer be spared

for operations under Dutch control, so we were to head back to England.

After sheltering in Terschelling from a full gale, we had a rough passage

back to Ijmuiden where we had several memorable farewell parties with

our Dutch friends. A few days later I was demobilised at Chatham, and issued with a complete

outfit of civilian clothes. The three piece suit was brown with a herring

bone pattern, and there was a pork-pie hat to go with it; brown shoes,

a striped shirt and a perfectly horrid tie. One last travel warrant

to get me back to Ewell; and so I became a civilian again. While I was

in West Africa I received a letter from the Admiralty addressing me

as Lieutenant Begent RNVR. So perhaps I did get that promotion after

all....... War sees man at his worst - and at his best. Far more fortunate than many, my abiding memory is of a time when, just for a while, people thought less of their rights and more of their duty. JBB |

|

Begent Family Home Pages

Front Page |

Site Map | Our

Family | Jokes

| Calendar |

Quotes |

Fun Stuff |

Links | Contact

us | Visitors

Book