James Henry Begent 1893-1955 |

My grandfather Jim Begent served in the Royal Naval during the 1st World War. He was in the Royal Naval Division (RND) sent in 1914 by Churchill to Belgium to try and stop the advancing Germans. This was at a time before the trenches when cavalry officers rode on horse back. The British were forced to retreat and Jim escaped to neutral Holland where he was interned. Wearing civilian clothes smuggled in Red-cross parcels and with a forged pass hidden in a tennis ball he escaped, and hiding in the propeller shaft of a ship he made it back to England. He returned to the Navy, went to the Dardanelles and served on ships in arctic convoys. In the 2nd World War he was an Air Raid Warden in London during the Blitz. His true story is related below by my father John Begent based on Jims letters

written at the time. I still have these letters and memorabilia. |

| ANTWERP AND AFTER: A PERSONAL STORY OF 1914/15

At 10.55 a.m. on Sunday 2nd August 1914 the following telegram was received at Worthing Post Office; "To: Begent 7 Kingsland Road Worthing.

Thus began the First World War for my father, James Henry ("Jim") Begent, at the age of 20. Having been a member of the London Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve since 1912, the call was not unexpected. An Able Seaman at the outbreak of war, he had enjoyed his training as a break from his work as a clerk in the London, Home Counties and Midland Bank, and was a member of No.9 Company's Field Gun crew. A faded photograph taken during practice at Broxbourne, Herts shows him on top of the "wall" as the limber was taken over. Throughout the war he corresponded with his half-sister, Mrs.Georgina ("Georgie") Marchant, who had provided him with a home in Croydon while he was working in London. She kept many of his letters, and a few years back these passed into my possession. What follows is based on them. The first letter from him is from Mess 4, H.M.S. Egmont, Royal Naval Barracks,

Chatham: On 20th August he sent a letter card with photos of "Ships of the Royal

Navy" to Georgie's elder daughter, Hilda (aged 8): TRAINING The next few surviving letters are headed "D25 Tent, D Company, Hawke Battalion. 1st Brigade, R.N. Camp, Deal".

It wasn't always tea. I recall him telling me that one night the lads, having drunk well, if not wisely, manhandled the slot machines on the pier down to the lower jetty, where they were found the next morning by the mystified staff. But there were already signs of more serious work ahead. "They have served us out with heavy marching boots so I had a couple of days footsoreness. We are expecting to get a few of our khaki clothes this week and also new rifles. I heard a rumour that we are going abroad in five weeks time but I cannot vouch for the truth of this." Nevertheless, there were more immediate concerns: "I should very much like you to make us a bread pudding, with plenty of currants and fruit in it; it would go down alright as it's sometimes jolly cold here, almost freezing at night." Georgie obliged. On 17th September he wrote: "Received pudding and tart and soon demolished them. Thanks very much. Today it is raining in torrents and the wind is - well, it's a gale and you can hardly stand against it. Yesterday we had a 12 mile march and I've got a small blister to get on with. Still, it's very nice out in the Kentish country." She sent another food parcel: "Thanks very much for the parcel which I received at dinnertime today. I opened it and five minutes later it was all gone. We were hungry after a forced march....we ran nearly all the way." As events proved, the forced marching practice was not misplaced. THE SIEGE OF ANTWERP Before continuing Jim Begent's own story, it is first needful to put the events into the context of the progress of the war in France and Belgium as described in Winston Churchill's book "The Great War". After the German advance had been stopped at the Battle of the Marne in the first week of September 1914, there began what became known as the "Race for the Sea" in which the left wing of the French and the right wing of the German armies sought to outflank each other, so that the fighting moved ever further north towards the Channel coast and the vital ports. Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, realised the importance of Antwerp. "Antwerp was not only the stronghold of the Belgian nation; it was also the true left flank of the Allied front in the west. It guarded the whole line of the Channel ports. It threatened the flanks and rear of the German armies in France....... No German advance to the sea coast, upon Ostend, upon Dunkirk, upon Calais and Boulogne seemed possible while Antwerp was unconquered." His views were shared by Lord Kitchener, the new Secretary for War. Brussels had fallen to the Germans on 20th August. Thereafter Belgian and German troops remained in contact along Antwerp's outer fortress defence line until 28th September when these forts came under heavy bombardment from German 17" howitzers. The siege of Antwerp had begun. Kitchener made plans to support the Belgians, including the despatch of two 9.2" heavy guns. But on the evening of 2nd October the British Government was alarmed by a report that the Belgians had decided to evacuate Antwerp. Churchill himself went to Antwerp the next day to persuade them to change their minds. Promised help, they did; at 6.53 p.m. on Saturday 3rd October Churchill sent a telegram from Antwerp to Kitchener outlining the agreement reached with the Belgian government, and including this request: "...... pray give the following order to the Admiralty: Send at once both Naval Brigades, minus recruits, via Dunkirk, into Antwerp, with five days rations and 2,000,000 rounds of ammunition, but without tents or much impedimenta. When can they arrive?" Churchill had his answer the next morning, Sunday 4th October, in a telegram from the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis Battenberg, timed 10.30 a.m.: "The Naval Brigades will embark at Dover at 4 p.m. for Dunkirk, where they should arrive between 7 or 8 o'clock. Provisions and ammunition as indicated in your telegram." The choice of the naval brigades was not fortuitous. Realising that on mobilisation the Navy would have many thousands of men in their depots for whom there would be no room in ships, in 1913 Churchill had proposed the formation of three brigades, one composed of Royal Marines and the other two of men of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and the Royal Fleet Reserve. The intention was to use these brigades for home defence in the early stages of the war, but when in August 1914 Kitchener began the formation of his first six new army divisions, Churchill offered him the Royal Naval Division; the offer was accepted. Meanwhile Churchill went to view the front for himself. As he later wrote: "Antwerp presented a case, till the Great War unknown, of an attacking force marching methodically without regular siege operations through a permanent fortress line behind advancing curtains of artillery fire. Fort after fort was wrecked by the two or three monster howitzers; and line after line of shallow trenches was cleared by the fire of field guns." On the morning of the 4th. armoured trains with naval guns, and manned by British naval gunners, went into action against the Germans. That evening Churchill visited a contingent of 2000 Royal Marines that had arrived in Antwerp the same morning. They were already engaged with the Germans in the outskirts of Lierre. The Naval brigades were expected in Antwerp on the evening of the 5th., and at the special request of the Belgian staff they were to be interspersed with Belgian divisions "to impart the encouragement and assurance that succour was at hand". But Churchill himself had no illusions about his own position: "I had also assumed a very direct responsibility for exposing the city to bombardment and for bringing into it the inexperienced, partially equipped and partially trained battalions of the Royal Naval Division. I felt it my duty to see the matter through." Monday 5th October was a day of continuous fighting. The Germans made some progress, but a counterattack by the Belgians and the Royal Marines under the command of General Paris R.M.A. almost restored the line along the River Nethe. The Germans, however, maintained a foothold north of the river, and the Belgians made a further counter-attack on the night of the 5th/6th to remove them. The attack failed, and the Belgians retired. The Naval Brigades arrived on the morning of Tuesday 6th. General Paris was heavily involved in the fighting, and he could not assume their command. So Churchill took over. With the agreement of the Belgian HQ he ordered that the Naval Brigades should be stopped four miles short of their original destination as a support and rallying line for the Belgian troops who were falling back. By midday the three Naval and Marine Brigades were drawn up with the Belgian Reserves astride the Antwerp-Lierre road on a line between Contich and Vremde. The expected attack did not come, and the Brigades moved forward and took up new positions nearer to where the enemy had halted. But the situation continued to deteriorate, and at 10.37 p.m. that night Churchill reported to Kitchener that an general retirement on the inner line of forts had been ordered, adding that: "The three naval brigades will hold intervals between the forts and be supported by about a dozen Belgian battalions." Churchill left that night to return to England via Ostend.

"On Sunday Oct.4th our Brigade [the 1st.] left Deal for Dover whence we embarked for Dunkirk. We arrived there on Monday and on that night took the train the Antwerp. We did not expect to get to Antwerp without meeting the enemy, but we arrived safely on Tuesday morning [i.e. the 6th] and were joyously received by the Belgians. Our maxim gun section was first billeted in a barn, but we had not been there very long before we had orders to move off to the trenches. That night we slept by the roadside with artillery pounding away on all sides, not much sleep you bet." Although it was not dated, it must have been on the morning of the 7th that Jim Begent wrote a hurried postcard to "Georgie" from "Boorsbeek, near Antwerp": "........ The Brigade is helping to repel the siege of Antwerp. We have had very little sleep but food is alright. The Belgians are very pleased to see us & very good to us. We expect to fight very soon. Germans 4 miles off and shells are coming and going....." This card eventually reached London on 2nd December, bearing a postmark "PUTTE 23 Nov 14". There are two Puttes in the Low Countries. One is in Belgium, a few kilometres east of Malines (Mechelen), but this was already behind the German lines when the card was written; in any event, the German authorities would hardly have sent it on to England. The other Putte lies due north of Antwerp, just over the Dutch border, but to the east of the Scheldt. One can only assume that a kind Belgian found the card after the fall of Antwerp and arranged for it to be carried over the border into neutral Holland and posted there. But to continue with the account in the letter of 15th October: IN ACTION "On Wednesday morning [the 7th] we took up our position in the trenches which stretched between the forts. The line of our first Brigade stretched for about 2 miles. All day the heavy guns were working while we made the trenches stronger and more shrapnel proof. All day and all night the shells screamed and burst overhead, but without damaging us very much. We were up all night watching and waiting - with loaded maxim and rifles - for an infantry attack; although we had many alarms the attack did not come off. By Heavens, it was an experience that first night under fire. In front of the trenches about 100 yds away were vicious barbed wire entanglements through which passed electricity of high power so even if the Germans had reached them I don't think they would have stood a chance of getting through. On Thursday [the 8th] we made the trenches much stronger in case they used Lyddite shells on us and because we knew that there would be a terrific artillery duel. We expected some British heavy artillery [the 9.2's spoken of by Churchill - see above], but they never came, and all we had were the forts, the guns of which were not half as good as we had believed, and the Belgian artillery which was old and hopelessly outclassed by the Germans. That day the firing was terrific and the "damned Germans" used those 17" guns and bombarded the town over our heads. We could hear the low drone made by the great shells as they passed high overhead. They did terrible damage in the city, causing it to break into flames and killing many poor refugees, helpless men, women & children. This day I was as near death as I have ever been. We, the maxim section, six of us went along the line in our motor lorry in order to get some more guns and ammunition. The road we had to go along had Belgian batteries on either side of it; the Germans appeared to have got the range as every now and again a shell would come whizzing overhead. We got safely along the road as far as we had to go, & had left the lorry & were going up the lane towards the lines when there was a bang & we saw in a field just ahead of us a cloud of smoke arise, then another bang & shrapnel burst all over us, but with marvellous luck none of us were hurt. We beat a hasty retreat and safely reached our own lines. Later on we fetched the guns & that night we had three ready to let out 400 rounds a minute at the Germans, but unfortunately we never used them. At 9 o'clock that night (Thursday) we were given orders to retire so we dismounted our guns & rushed them up to the lorry; meanwhile a party of marines arrived just to keep the fire up while our men left the trenches, & very soon afterwards Hawke Battalion started off on one of the most awful marches I should think it possible to experience. We marched right along past the Belgian batteries who were pounding away at the Germans & the shells were bursting all over the place, many of them quite near; it made me wonder how long it would be before we were struck down. That duel was the most awful thing I have ever seen; the country around was in many places in flames & and in the lurid glare we could see the gunners hard at work. Twice I saw a German shell burst right in the midst of a battery & and then all was quiet; all killed I expect. How far we marched through the country I don't know, but all night we passed burning farms, & batteries. Here and there we would meet two or three Belgians marching away from the fight, and here and there we would pass dead and dying men by the roadside. We continued until we passed some blazing oil tanks, & then we began to march beside the river. By this time a great many were feeling the strain & marched along as if they were dazed. I nearly went to sleep while marching, & got so fed up that I did not care one bit whether I survived or not, as along the docks the shells were bursting and smashing the houses. It was pitch dark here, & we almost had to grope our way. It was owing to this darkness that D company to which I belonged dropped behind & lost their way & have not been seen or heard of since, so heaven only knows what happened to them. My friend and I crawled under some railway trucks & joined up with the rest of our battalion. We thought the others were following but evidently they were not. However, we continued more dead than alive until we came to the Pontoon Bridge [over the Scheldt] which we crossed at 5 a.m. after marching for 8 hours. We rested for an hour at daybreak [i.e. on the 9th] & then continued our journey towards a place called St.Nicholas where we were to take the train for Ostend. We marched all day although we could hardly drag one foot before another, but just as we were nearing St.Nicholas we had to turn back as we were warned of the presence of a large body of Uhlans [German cavalry]. We marched back about 2 miles, & were then told that we had 4 miles to march in 3/4 hour or we should probably be cut off by the evening. Well, despite our feelings we marched like demons & almost reached our destination when a Belgian brought news that the Uhlans were just in front. We spread out in extended order & waited, but after a couple of shots the Uhlans, five in number, scooted when they saw how many of us there were, & we arrived safely at St.Gillis where we were going to take the train. Our commander heard however that the Germans were cutting off the line so he would not let us get on. It was lucky for us that we did not as that train was blown up with all the refugees on it. With no other course open we marched a further 4 or 5 miles into Holland where we had to lay down our arms." Churchill later wrote: "Only weak parties of Germans ventured beyond Lokeren during the night of the 9th-10th to molest the retreat of the Antwerp troops. The 2nd Belgian Division and two out of the three Naval Brigades came through intact. But the railway and other arrangements for the rear brigade [the 1st.] were misunderstood, and about two and a half battalions of very tired troops, who through the miscarriage of an order had lost some hours, were led across the Dutch frontier in circumstances on which only those who know their difficulties are entitled to form a judgement." [It should be added that not all of them were lucky enough to reach neutral Holland; some were caught by the advancing Germans and ended up in Doberitz prison camp near Berlin.] Was it all worthwhile? Churchill thought so. His strongly held view was that but for the resistance offered at Antwerp and for the measures taken to prolong that resistance the considerable German forces engaged would have been free to carry out an almost uninterrupted march upon the Channel ports: "Had the German Siege Army been released on the 5th and, followed by their great reinforcements already available, advanced at once, nothing could have saved Dunkirk, and perhaps Calais and Boulogne. The loss of Dunkirk was certain and that of both Calais and Boulogne probable. Ten days were wanted, and ten days were won." The new internees spent their first night of captivity (the 9th/10th) by the roadside, They were then taken by train to Terneuzen, and thence by steamer to Flushing (Vlissingen). Here Jim Begent sent another postcard to "Georgie" dated October 10th.: "After a most adventurous time we have - some of us - arrived here [Flushing]. I don't know where we are going. Had a pretty rough time....." The card has a coloured picture of the main street of Borsbeek, which he must have bought 3 or 4 days earlier, and carried with him on the long retreat. His letter of 15th October concludes: "We settled comfortably into an engine shed for the night [i.e. in Flushing] but were awakened about 10.30 p.m. & put aboard a train in which we spent 12 hours and eventually arrived at Groningen, a town of considerable size in the very north of Holland. We are quartered in a Military barracks [the Infanterie Kazerne]........ A few days later he wrote to Georgie: INTERNMENT "....... I have not yet had time to write you a full account of my experiences, but I have written one to Dad. We are living in the military barracks at Groningen and there are about 1500 of us here. We sleep on straw beds and have one blanket each. There are 15 of us in an attic. It isn't bad but it's rather bare. We have three meals a day, but they are not very satisfactory. One can quite understand it as there are about 25,000 Belgian troops as well as thousands of refugees in this country. We get at breakfast-time coffee and a 1lb brown loaf, which has to last us all day, and about 1/2 oz. of margarine. Our dinners consist of about 2 ozs. of fat meat and either spuds or black beans, very filling but not sustaining. For tea we get tea and some horrible stuff they call cheese. Both the coffee and the tea have no sugar in them and very little milk. We can buy margarine, sugar, chocolate & apples etc. in the canteen, but you cannot get them when you have no money. All my kit was lost at Antwerp & I had nothing except what I stood up in; but the Dutch have given each of us a striped jersey & a pair of pants to go on with. At present we are not allowed liberty, and have no exercise, so you can guess I don't feel very happy, but no doubt things will improve. We shall have to stop here until the end of the war unless Germany violates Dutch neutrality, which I consider very probable. I have today made an allotment which means that if the Admiralty pay us during the time we are here you will receive monthly through Selhurst Post Office 2/3rds of my pay or about £2 a month.........." Of course, it took some time for these letters and the card from Flushing to reach England, and meanwhile Georgie had instituted her own enquiries after the fall of Antwerp. From Walmer camp she received the following note dated Oct.19th 1914 "From - O.C. 1st Brigade To - Mrs. Marchant Walmer Camp 33 The Crescent Croydon Replying to your letter, J.H.Begent has not returned to camp and is, therefore, probably interned in Holland A.H.Travers Lt.Cdr. " A week later she had an official printed communication from the R.N.D. Record Office, 47, Victoria Street S.W., dated October 24th 1914 and addressed to "The Next of Kin of James Henry Begent, A.B., R.N.V.R." "I regret to inform you that I have received a report from the Foreign Office that James Henry Begent, A.B., R.N.V.R., London 9/2967, serving with the R.N.Division, has been interned at Groningen in Holland, where he will remain until the end of the War. Separation allowance and any allotment he has made will continue to be paid. If he has made no allotment, he will be given an opportunity of doing so. Letters and parcels intended for him will be exempted from postage, and should be addressed as follows:- Name and Rating, British Sailor (R.N.D) Interned in Holland, c/o General Post Office, Mount Pleasant, London. I am, Your obedient servant, (signed) A.Randall Wells Once the mail link was established, letters (including small sums of money) and parcels of food and tobacco began to flow from Georgie and other relatives. Conditions gradually improved; entertainments and sporting activities were organised. On 18th January 1915 the internees moved into new quarters;

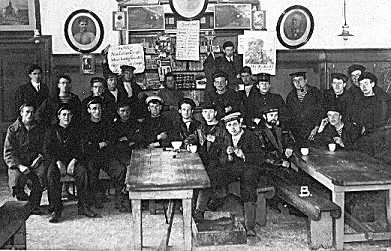

A "Harriers" club was formed, and members were allowed to go on cross country runs, accompanied by an armed Dutch military cyclists. Men were allowed a few hours leave in the town, and good relations were soon established with the local population. On 27th January 1915 Jim Begent wrote to "Dear Georgie": "I was very pleased to hear from you, also to receive the £1. I have been "ashore" twice since it arrived so I'm looking forward to the next £1 as I again go on leave in about a week's time. It was a change to be able to walk about free & to be your own master for 3 hours from 1.30 to 4.30 p.m. The first time last Friday we strolled about the town and visited the cafes & did some shopping. A good many people here speak English and of those that do not some speak French so I can make myself understood. Everybody is civil to us, and we have a good time. On Monday I went ashore with one of our No.9 [pre-war RNVR company] men, Bale, who is a cashier in the London, City & Westminster Bank, and we visited a Dutch gentleman whom we met in the barracks, Heer Dobbinga, who is an art dealer & a painter. We had afternoon tea with him. He used to visit the barracks daily until his pass was recalled, so now we visit him. His house is filled with antiques of every description. Later we met four other No.9 men and had a good feed, steaks etc. & liqueurs." On 19th March Jim reported: "I am writing this [letter] at a Concert given by some Dutch people to us, and it's a very good concert, too. Our "Follies" [the camp concert party] gave a show at the local theatre & had a great reception; incidentally they were presented with a laurel wreath, an honour over here." Contact with Heer Dobbinga continued, and on 9th May Jim Begent and his friend Bale were able to entertain friends in the camp itself: "Today being Sunday we had some friends in to visit us , who had tea with us in our pavilion which has been fitted up as a tea-place for visitors. We had in Mr.A.J.Hamers & his sister, & M.van Huffell (a Belgian from Antwerp) of the Hotel Seven Provincien where we go to dinner when we get out. Mr. Hamer speaks English but we have to converse with the Belgian in French. Cricket & tennis have now started, & we are practising for a Gymnastic Competition on our Sports Days, June 2nd., 3rd. & 5th. Three of us have also started an allotment in the grounds and have been digging for the last two days."

"No doubt this all sounds very nice, and so it would be if it was in England; but unfortunately it isn't, and beneath this veneer of contentedness with one's lot there lurks dissatisfaction when one thinks of all the other lads fighting at the Front. No doubt you have already heard of the 2nd Brigade being in action at the Dardanelles. Two of the office [i.e. Midland Bank] men are with them." Concern over the well-being of his former colleagues, both of the Midland Bank and the RNVR, who were on active service was a feature of his letters at this time. Indeed, for a while he managed to correspond with a Bank friend who was in the British Expeditionary Force on the Western front with the Rifle Brigade, and arranged for Georgie to send him tobacco and chocolate. Above all he wanted to get to sea with the Royal Navy. After the Battle of the Dogger Bank in January 1915 he wrote; "What do you think of the last Naval victory - fine, wasn't it? Davies of my section in London is in the "Lion" with several more RNVR men, & one of our Thread[needle] St. [branch of the Midland Bank] staff is in the "Princess Royal" with more RNVR men. [Both ships were battle cruisers; the former was badly damaged in the action; the latter was lost at the Battle of Jutland, 31st May 1916] That's the second time they have been in action. I wish I were with them......" ESCAPEIt was therefore no surprise that he began to think seriously of escape. It had been tried. On 12th March Jim had reported: "Two more of our men, with outside influence, succeeded in getting home about a week ago, & the Dutch are now watching us very closely. We are mustered three times daily, and all our parcels have to be opened by us in the presence of a Dutch official. I am living in hopes of something turning up this summer, and I think there will be." But not all would-be escapees were successful. On 8th April Jim recorded that: "Two fellows tried to escape last Sunday & were caught at Arnhem about 120 miles from here, and two who tried on Wednesday have been caught at Rotterdam. They watch us very closely in this country." Nevertheless, on 28th May 1915 Jim wrote to Georgie's husband, J.F. ("Frank") Marchant, in the following terms; the importance he placed on it can be judged from the fact that it is the first letter since that of the 15th October 1915 to be written in ink - all the rest were in pencil or indelible pencil: "Dear Frank "I am writing this letter to you instead of to Georgie as to get the gear over here that I am asking for requires a good deal of care in packing and sending and also attention to detail. As I am fed up with this place I shall, if opportunity offers, attempt to regain England. I want you to send me out some clothing, but as our parcels - or, at least, most of them - are examined, I must go carefully or I shall not get them through. The chief matters will be 1. That the parcels are small 2. That I know when to expect them. The clothes that I shall require will be my light brown raincoat, my best pair of striped trousers & braces, my dark grey coat & waistcoat, a soft felt hat - which you will have to buy, dark brown or dark grey, size 6 3/4 - a soft collar, size 15 1/2" a dark tie, studs & and a pin for the collar. In the first parcel put the trousers, collar, tie, pin and hat. Roll the collar up very tightly in the trousers, tie with string, then into brown paper of two or three thicknesses so that the clothes will not show if the outside paper is torn. Address in the usual way & put some green sealing wax on the knots, and put two or three small blue pencil crosses on the paper. In the second parcel put my light brown raincoat & the waistcoat. In the third put the coat. In both these latter parcels make them as small as possible, & do just the same as the first. Then three days before you send them, send me a postcard e.g. telling me how Georgie & the kids and yourself are etc. - Then I shall know that three days from the date you put on the card they [the parcels] will be sent off, & therefore know when to expect them. I suggest you send them together from the G.P.O. London; also send the card from there. Well, if you carry out in detail the instructions which I have given I think I shall have a reasonable chance of getting them through undetected. Do not mention anything about this in any letters that G. or yourself may write in the future; not unless I write to you first." Frank carried out these instructions. Knowing approximately when the parcels would reach Groningen Jim was able to warn fellow internees on duty in the post office hut to look out for them; the green sealing wax and small blue crosses were for identification purposes. While the attention of the Dutch supervisor was distracted the three parcels were thrown out of the window into the long grass behind the hut. From there Jim was able to recover them undetected, and thus avoid having to open the parcels in the presence of a Dutch official. By the end of June preparations for the escape were almost complete. On Friday, 1st July 1915 he wrote: "Two men in our mess, Hapgood & my friend Reg Cooper left last Sunday & have arrived in England. We have had telegrams from them & Reg is writing to me later. I hope, all being well, to get to Croydon sometime this month. If I don't it will be 14 days in cells. There are about ten fellows in now, & it's getting damn difficult to get out of the Camp & they watch us very closely. Still, "nothing ventured, nothing gained", and one can but try." From now on I must rely on my own memory. Only once did I persuade my father to tell me his story, and that was when I was about 15 - it may be that the conversation was triggered by the news of the German invasion of Holland & Belgium in 1940 - and long before these letters came to light. He was accompanied by a friend - I think it was his messmate, Ernie(?) Bale, mentioned above, but I cannot be sure - who had obtained civilian clothes in the same way as Jim. Their first problem was to get out of the camp in such a way that their absence would not be noticed until the next muster. As a condition of being allowed out of the camp on leave the internees had been required to give their parole that they would not try to escape. If it was discovered that a man who had escaped to England had broken his parole he was promptly sent back to Holland. Jim and his friend therefore had to give formal notice of the withdrawal of their parole. This not only meant the stoppage of their leave, but also made them marked men. However, they were still allowed outside the camp for one purpose - to visit the local public baths. Such visits were made in groups escorted by a Dutch soldier; each man was issued with a pass which had to be shown on leaving the camp and handed back on re-entering. This was their opportunity to escape. Wearing civilian clothes under their uniforms Jim and his friend marched out of camp with the "Baths" party, escorted by a Dutch soldier. Once clear of the gates they stuffed their passes into a tennis ball which had had a slit cut in it, and threw the ball back over the wire. There it was recovered by two other internees who, already armed with towel and washing bag, sprinted up to the gates and, showing the passes, explained that they had got left behind. Allowed through, they ran down the road after the Baths squad in the sight of the guards and tagged on to the end of the squad. At a convenient point en route to the Baths the attention of the escort was distracted, and Jim and his friend slipped away from the party to a pre-determined spot where they could shed their uniforms, hide them and head for the station in civilian clothes in time to catch the train to Rotterdam, first buying their tickets with Dutch guilders. The deception worked. The escort returned with the same number of men he had started out with; every man handed in a pass when he re-entered the camp and the number of passes received tallied with the number issued. The journey was uneventful; whenever other passengers were around Jim and his messmate kept silent or pretended to sleep. On arrival at the main station in Rotterdam they had been told to look out for a tall man wearing a striped blazer and a straw boater, and carrying a walking cane. They were to follow him when he left the station; under no circumstances were they to speak to him or get too close. He was there, sure enough, and they followed him through the streets. They had one bad moment when a large Dutch policeman took an interest in them; having got so far they decided that if he tried to stop them they would knock him down and make a run for it. Happily, his attention was distracted by something else, and they breathed again. Reaching the docks the man in the straw boater led them along a quay and as he passed the gangway of a ship flying the Red Ensign, without looking round, he pointed to it with his cane. They took the hint and boarded the ship. They were expected, and were at once taken to the bowels of the ship. An inspection manhole was opened, and they were put into the propeller shaft tunnel and told "Keep your heads down". The cover plate was then bolted back in place over them, and they lay in the dark. Their incarceration was, of course, a precaution in case the Dutch authorities, who must have been aware by then that they were missing from the Groningen camp, decided to search the ship before it left. [I only wish that I had known enough at the time I heard his story to ask my father about the escape organisation which must then have existed; it would have had to include "Our man in Groningen"; could it have been the friendly Heer Dobbinga, the antique dealer and painter, or A.J.Hamers or M.van Huffel who had been entertained to tea on 9th May? There was also a British Consul in Groningen at the time, a Mr. J.M.Prillevitz, but it is unlikely that he would have jeopardised his diplomatic status by being directly involved. Whoever it was, someone in Groningen notified our agents in Rotterdam to expect the two escapees on a certain train, so that a guide could be arranged and a ship provided]. After a while the ship got under way, and the point of the warning to keep their heads down was all too obvious as the giant shaft began to revolve. Once clear of the port the cover was opened and they were taken to the crew's quarters where, after being allowed to clean up, they were given white jackets and told that for the duration of the voyage they would work as stewards. This was to provide a cover for them and explain their presence on board, which otherwise might have been reported to the Dutch authorities, and caused difficulties for the skipper when next he was in Rotterdam. As Jim said, "We did our best, but we weren't very good stewards". On arrival at Harwich the next day they were both taken to the police station so that checks could be made on them, and they were interrogated by a Naval Intelligence Officer before being allowed to take the train to London. Jim Begent's obituary in the Midbank Chronicle (the Midland Bank's house magazine) after his death in July 1955 mentioned his escape from internment "disguised as a ship's steward" and added "it is said that he arrived back at Head Office penniless and was assisted by a friend with money to get home [i.e. to Frank and Georgie Marchant's house at Croydon]". BACK TO SEA After a short period of leave, Jim Begent returned to R.N.Barracks, Chatham, where he made sure of being drafted to sea by qualifying as a Signalman. He joined the old battleship "Mars" and went to the Dardanelles (another Churchill project) in time for the evacuation. (According to Churchill's account in his book "The Great War", if Commodore Keyes' plan had been adopted the "Mars" and other elderly battleships fitted with "mine bumpers" and accompanied by sweepers would have been used to force the Narrows ahead of the Fleet; hopefully, half of the ships would have got through to the Sea of Marmora and cut the Turkish communications. In the event, it wasn't.) By 2nd February 1916, Jim was back at Croydon. His next posting was as a Leading Signalman in the 25 year old cruiser "Intrepid" in the White Sea Squadron, charged with keeping open the supply lines to Imperialist Russia via Murmansk and Archangel. (Later the Intrepid gained fame as one of the blockships in the 1918 Zeebrugge raid). In 1917 he was serving in the gunnery training sloop "Pembroke" working out of Chatham; for the rest of his life he suffered from ear trouble consequent on being on the open bridge during the firing of the foc's'le gun. He finished the war as a Yeoman of Signals, instructing at the Signal School at the Crystal Palace. On demobilisation he returned to the Midland Bank (now HSBC), and married in 1923. In the Second World War he was an Air Raid Warden during the Blitz. In 1942 he was commissioned as a Temp.Lieutenant R.N.V.R. (Special Branch) and was the First Lieutenant of the Kingston-on-Thames Sea Cadets for four years. His love of the sea and the Royal Navy never faded. Ewell, December 1988 John Begent Postscript Oct 2000: With thanks to for the Groningen Camp photos from Nick Johnston whose grandfather Reginald Wright was in Collingwood battalion and great uncle Ashley Wright in Hawke. Information from RNVR naval records on Jim Begent and his pals mentioned above - kindly provided by John Morcombe as follows L9/2967 AB Jas. Henry Begent RNVR Joined Hawke Bn. 7/9/14. Escaped from Holland between 6/7/15 & 16/7/15. HMS "Europa" (Base ship Mudros) 25/11/15-7/3/16. Listed in the 1914 Star roll as receiving his medal 17/6/19 at the HQ RNVR London; & his Clasp & Roses to the 1914 Star 21/12/20. (Also entitled to the British War & Victory Medal) L9/3251 LS Stanley Hapgood RNVR Joined Drake Bn. 22/8/14. Escaped from Holland between 26/6/15 & 6/7/15. 23/3/16 Deserted from 2nd Reserve Bn. RNVR, Blandford. Enlisted in Army 11/4/16, promoted to Temp. Lt. 1914 Star was forfeited, but restored in 1924. L9/2171 AB Reginald Seymour Cooper RNVR Hawke Bn. 914. Escaped from Holland between 26/6/15 & 6/7/15. L9/2491 AB Ernest Edward Bale RNVR Hawke Bn. 1914. Did not escape. John Morecombe's RND site can be found at www.jackclegg.com Further information on the 'Timbertown' internment camp in Groningen can be found on Menno Wielinga's site at www.war1418.com/timbertown/homepage.html Michael Robinson has produced an eBook of the Camp magazines which make fascinating reading http://www.epubbud.com/book.php?g=JQ8GLQEZ

| |

Front Page | Site Map | Our Family | Jokes | Calendar | Quotes | Fun Stuff | Links | Contact us | Visitors Book

"It's

much the same as ever here, drilling all day or digging trenches, and

liberty in Deal two evenings out of four. Deal is a fairly quiet place

and adjoins Walmer, and between the two the Front or Parade is about

3 miles long. We usually go in to have a good tea at one of the restaurants."

"It's

much the same as ever here, drilling all day or digging trenches, and

liberty in Deal two evenings out of four. Deal is a fairly quiet place

and adjoins Walmer, and between the two the Front or Parade is about

3 miles long. We usually go in to have a good tea at one of the restaurants." What

followed is described in a letter Jim Begent wrote on 15th October to

his father in Worthing:

What

followed is described in a letter Jim Begent wrote on 15th October to

his father in Worthing: "Huts

about 100 yards long, 20 yards wide and 25ft. high, lighted by electric

light and warmed by coke stoves. They are capable of holding 400 men

each. There are four large huts, one for each battalion and one for

a main hall. Then there are numerous smaller ones, such as those for

the post office, bathroom, stores, workshops etc. They are erected on

an old football field, & form quite a small town - of which I hope

we shall not long be the inhabitants. The whole is encompassed by a

barbed wire fence about 6 ft. high, with lights & sentries at intervals."

"Huts

about 100 yards long, 20 yards wide and 25ft. high, lighted by electric

light and warmed by coke stoves. They are capable of holding 400 men

each. There are four large huts, one for each battalion and one for

a main hall. Then there are numerous smaller ones, such as those for

the post office, bathroom, stores, workshops etc. They are erected on

an old football field, & form quite a small town - of which I hope

we shall not long be the inhabitants. The whole is encompassed by a

barbed wire fence about 6 ft. high, with lights & sentries at intervals." But

Jim was getting restless. The same letter goes on:

But

Jim was getting restless. The same letter goes on: